The Man Who Laughs

4th November 1928

When a proud noble refuses to kiss the hand of the despotic King James in 1690, he is cruelly executed and his son surgically disfigured.

Paul Leni

Mary Philbin, Conrad Veidt, Julius Molnar, Olga Baclanova

1h 50min

Whilst Silent cinema is, on the whole, relegated for those with more than a passing interest in film history, there is a rung of countless films made in the formative years of cinema that pass un-watched and forgotten by all but the most dedicated movie enthusiasts. If you have seen or heard of any silent films, the likely handful are either German Expressionist films like Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari and Metropolis, or those produced by Carl Laemmle and Universal like The Phantom of the Opera or The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which starred ‘The man with a Thousand Faces’ Lon Chaney Sr. Or possibly still the most famous works of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton or Laurel & Hardy.

The Man Who Laughs falls amongst those made by Univeral by founder Carl Laemmle, but has oddly never received the same recognition as the work involving Lon Chaney, despite in some ways being superior. Not that The Man Who Laughs has been completely forgotten, but it seems largely remembered now for being the inspiration for Bob Kane and Bill Finger in creating Batman’s arch nemesis the Joker. Either way it certainly isn’t one of the most remembered silent films of all time, despite being a large production.

Directed by German Expressionist filmmaker Paul Leni, The Man Who Laughs blends the more creative use of camera and light from his homeland with the lavish production budget of a Universal picture to create both a narrative and visual experience of high quality. As mentioned previously this is actually in contrast to some of the more well known Universal silent films with Lon Chaney Sr, which whilst being undeniably classic and influential, clearly had extensive production troubles. Both Hunchback and Phantom cycled through multiple directors before Chaney supposedly took over, resulting in a much more pedestrian camera. The Man Who Laughs does not have this problem. It’s clearly directed with purpose and vision and feels largely more polished than most other silent films I’ve seen. Obviously you can’t expect a flying camera and complicated dolly shots, the cameras back in these days were much too cumbersome for such feats, but there’s a real eye for composition here, and whenever movement is used, you’re going to notice.

You may be mistaken, like me, that The Man Who Laughs is a horror story. Despite its intrinsically frightening protagonist and some horrific scenes, the film plays much more as a fairy-tale romance and in fact, is a similar story to The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The plot follows Gwynplaine (Conrad Veidt) who’s surgically disfigured as a child because his father openly rebelled against the king. This disfigurement results in Gwynplaine bearing a permanent smile across his face. Whilst near death he is luckily taken in by a carnival owner, and grows up to be an honest and kind man despite constant torment and bullying. He falls in love with a blind carnival performer called Dea (Mary Philbin), but never feels worthy enough of her love because of his disfigurement. Meanwhile the cruel jester of the now Queen monarch gets wind that Gwynplaine survived and seeks to destroy or corrupt the laughing man.

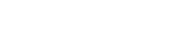

These type of silent films always possess a strong atmosphere above anything. They feel more like dreams or nightmares over traditional stories. How much you get out of them relies on you as an individual. If you’re willing to work and let your imagination fill in the details, it can be an immensely rewarding experience. Conrad Veidt delivers a hypnotic performance that really stands the test of time especially. Despite having a constant grin (with the help of some painful dentures) he expresses so much with his face. You can see him actively fighting against the smile as he tears up in scenes, and the way he hides his mouth is deliberately childlike. The rest of the cast are also thankfully distinctive. Silent films in particular relied on easily recognisable faces and The Man Who Laughs doesn’t disappoint in this regard. Whether it’s the Queen, the conniving jester or common peasants, the actors chosen possess features that wouldn’t be amiss in exaggerated animation.

Eureka has lovingly produced this release, and for 1928, The Man Who Laughs looks stunning. There are two versions available on the disc: one has the original 1928 movietone score and the other has a newly recorded score by the Berklee School of Music. However I do have to confess that it is a struggle to get through it’s almost 2 hour runtime simply due to the decreased attention span of modern audiences. There are some simple but welcome extras included on the Blu Ray that detail some of the production history and place the film within the context of its time. It’s easily a worthwhile purchase if you’re a fan of silent cinema.

SPECIAL FEATURES

- LIMITED EDITION O CARD (2000 UNITS)

- 1080p presentation on Blu-ray from Universal’s 4K restoration

- Uncompressed LPCM 2.0 (stereo) score by the Berklee School of Music

- Uncompressed LPCM 2.0 (mono) 1928 movietone score

- A brand new interview with author and horror expert Kim Newman

- A brand new video essay by David Cairns and Fiona Watson

- Paul Leni and “The Man Who Laughs” – featurette on the production of the film

- Rare stills gallery

- A collector’s booklet featuring new writing by Travis Crawford, and Richard Combs

The Man Who Laughs is now available for the first time in the UK on-Blu Ray and can be ordered through the Eureka Store.

Polished production

Incredibly expressive performance by Conrad Veidt

Difficult to keep fully invested for 2 hours

Nice review, thanks!

However, Conrad Veidt made many talkies, in Germany, France, Britain and the USA. You may have heard of Casblanca?

Thank you David.

You are of course correct concerning Conrad Veidt. What I had meant to suggest was that neither Paul Leni and Conrad Veidt found major success in the talkies before dying. Veidt often found himself typecast in talkies and despite being in a major production like Casablanca, never broke out as a key player in talking pictures. I’ve edited the closing comment to better suit that. Thank you.

Camreras were not cumbersome by 1928, and some models were used long after the end of the silent era.