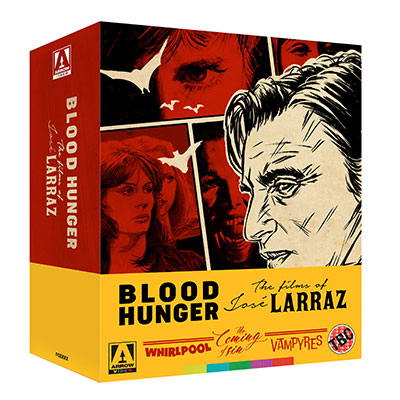

To celebrate the release of Blood Hunger: The Films of Jose Larraz, the head of restoration at Arrow Video James White speaks of his personal attachment to the project as well as revealing the stories of how the restoring of each of the three films was achieved.

I first discovered the cinema of José Roman Larraz in the same way that many others probably did, through the seminal book Immoral Tales, written by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs. This book was absolutely essential for anyone interested in European cult cinema and served as a primary reference for anyone hoping to learn more about the films of Jess Franco, Jean Rollin, Walerian Borowczyk and Robbe-Grillet, among others. But having been published in 1995, attempts to see the titles discussed would often prove to be a source of frustration, given how few of the films were accessible to view. More often than not, many of them were only available in bootleg form, often incomplete and of terrible quality. Most elusive of all were the films of José Larraz, who’s films (with the single exception of Vampyres) had all but vanished from the earth.

Then in 2016, Pete Tombs’ own Mondo Macabro and the BFI Flipside labels released simultaneous Blu-ray editions of Symptoms, Larraz’s 1974 British horror film. The film had been newly restored by Belgian Cinematek and was sourced from the original negative, rediscovered at the BFI Archive after long believed lost. The film was a revelation to me and many others who were seeing it for the first time. Although Symptoms invited comparisons to such films as Repulsion in terms of its plot, the film’s unique spell lay both in its casting of Angela Pleasence as the mentally fragile protagonist, and in how Larraz brought a unique outsider’s eye to capturing the British landscape, presenting an unrelenting dreamlike atmosphere that shunned the neat and logical narratives of say, the Hammer or Amicus films at the time. The film was really like nothing else from the era, and its haunting ambience remained with the viewer long after the film was over.

Given the renewed interest in Larraz’s films, it was only right that we at Arrow would restore his very first feature, Whirlpool (1970). Prior to this film Larraz had never directed, having worked as a comic-book writer and fashion photographer. So it was surprising to see the same visual sensibility I saw in Symptoms almost fully formed in this earlier film. Whirlpool’s primary influences are fairly obvious – Blow Up and Peeping Tom both loom large here – but although Whirlpool is a much cruder film in many ways (the film was shot on an extremely low budget and the soundtrack was post-synched in Rome), it distinguishes itself with a heavy atmosphere of dread and mystery throughout. It also brings a frankness to its erotic content that stands in stark contrast to the tittering repression exhibited in most British exploitation films of the period.

Locating materials for Whirlpool took some detective work, but we finally located the film’s original materials in UCLA’s archive, which included the film negative and optical soundtrack. We scanned the materials at Deluxe’s EFILM facility and graded and restored the film at R3Store Studios in London. Available references to work from were scant, but the materials were thankfully in good condition and we were able to arrive at the closest approximation to the original look and feel of the film we deemed possible. We remastered the audio at Deluxe’s Audio facility in Los Angeles and were able to remove most of the surface noise issues while preserving the atmosphere of the soundtrack, including Stelvio Cipriani’s haunting score. Once the main restoration work was completed we expanded our search for any existing elements for the UK/European version, which included a couple extraneous shots and most notably, a voiceover during the final scene, but sadly no materials could be found. These differences are explored in an extra on our release, “Variations on Whirlpool”.

As with Symptoms, Vampyres (1974) is a film unlike any other films made in Britain at the time, with its unrestrained marriage of sexuality and violence bringing a primary blood-lust to British cinema that simply hadn’t been seen before. This combination proved too much for the censors, who demanded Larraz cut his film throughout in order to pass classification. I had only seen Vampyres on video before, so I welcomed the opportunity to give the film its proper due with a new restoration of the complete uncut version from the original materials. Fortunately the film’s producer Brian-Smedley Aston had kept hold of the original negative which was both in very good shape and complete & uncut, with the the exception of a portion of the final reel, which we were able to source from a 35mm CRI element. All scanning, grading and picture restoration work was completed at R3Store Studios, with great care taken during the colour grading to maintain its gothic atmosphere, while presenting the stark reds of the bloodletting in all their lurid glory. The soundtrack was remastered from the optical negative at OCN Digital.

Finally, we restored a Larraz title I had never seen a frame of prior to working on the film, The Coming of Sin (1978). This film, shot and produced completely in Spain, is really more of an erotic thriller than a horror film, although it maintains Larraz’s signature atmosphere of bleakness and dread throughout. The dislocation from reality is only further emphasised this time by the film’s use of light, film grain and a gauzy diffused texture. Materials were sourced from the Spanish licensors via Deluxe Madrid with the original camera negative serving as the primary picture element. Once again, references to work from were relatively nonexistent, but it was clear from examining the negative that the work to present the film’s unique look was achieved right there in the negative, and hadn’t been achieved through intermediate lab processing. After scans were completed at Deluxe, the remaining picture grading and restoration work was completed at R3Store Studios. Unfortunately the negative had retained some serious chemical damage which we could not completely remove, but aside from this the materials were in fairly decent shape. With regards to the audio, The Coming of Sin is a very quiet film, as little dialogue is actually spoken (a choice apparently made to conceal the nonprofessional actors’ limitations), making preserving the soundtrack’s atmosphere correctly all the more crucial. Fortunately the original magnetic reels had been kept and Deluxe Madrid was able to preserve the soundtrack with minimal tinkering.

Many people have helped make this project happen, including the restoration team at R3Store, Deluxe Madrid, EFILM/Deluxe Los Angeles, OCN Digital and the UCLA Film Archive. I should also like to thank Pete Tombs, both for his assistance during this project, and for his part in introducing me to the films of Jose Larraz a decade ago. Working on these Larraz films has been a truly eye-opening experience, one I hope to continue should the original materials surface for the remaining films in José Larraz’s output resurface one day. At the moment, the elements for many of his films remain shrouded in mystery, but my hope is that our work on these films will further his legacy and help bring about the rediscovery of those films that remain lost.

Blood Hunger: The Films of José Larraz available on Blu-ray March 25th from Arrow Video.

You can order it from Arrow’s official site: https://arrowfilms.com/product-detail/blood-hunger-the-films-of-jos-larraz-blu-ray/FCD1852